GSoC 2020 Final Report: Pointer Authentication Support in Ibex

This is the final report of the GSoC project on lowRISC. We have integrated pointer authentication into Ibex. This report summarizes Ibex work and LLVM work in the project.

Introduction

Hacker attacks aiming at overwriting control data including code pointers, data pointers, and return addresses in order to achieve arbitrary code execution are a serious threat for modern computer systems ranging from embedded systems to servers. To prevent or at least aggravate such attacks, many state-of-the-art desktop and server systems implement countermeasures like data execution prevention (DEP), address-space layout random- ization (ASLR), return stack protection, and even encryption and authentication of random access memory (RAM). The research community has also come up with more advanced proposals for guaranteeing control-flow integrity (CFI), some of which are also suitable for embedded systems with tighter energy and resource constraints. However, most CFI solutions deployed in state-of-the-art systems are rather primitive and today’s embedded systems hardly implement any countermeasures.

With pointer authentication (PA) being integrated into the ARMv8.3 processor architecture specification (optional extension for the ARMv8.3-A specification), a big step is made to add resistance against some of these memory vulnerabilities at least in high-end embedded processors targeting for example smartphones. ARMv8.3-A’s recent PA feature can efficiently mitigate pointer corruption. PA uses cryptographic message authentication codes (MACs) both checked and generated at runtime to protect the integrity of pointers. Compared to other countermeasures, it is considered a low-cost technique and is thus attractive for embedded systems and actively considered for standardization in other processor architectures such as RISC-V.

This project aims to perform a proof-of-concept integration of PA into Ibex. To our knowledge, this project is the first attempt at PA for 32-bit systems. We hope this project will be useful for security in the IoT era. PA actually needs to be accompanied by CFI - so far we have just focussed on PA and have not looked at integrating it with CFI. .

This document first describes the main challenge of integrating PA into a 32-bit embedded processor core followed by a description of how we addressed these challenges. And then, this document describes the new instructions and cipher circuits required to extend the Ibex processor pipeline with support for PA. In addition, as a software task, this document describes the compiler update task to automatically insert instructions for signing and authenticating return addresses. We chose LLVM as the compiler because LLVM can easily be extended and because it supports ARMv8.3-A PA. Some of this work can be re-used for this project. Finally, this document describes the evaluation results and conclusions.

Background

Pointer Authentication

PA is intended to check the integrity of the pointer with minimal impact on size and performance. PA conventionally takes advantage of the fact that the actual address space of 64-bit architecture is less than 64-bit and places a pointer authentication code (PAC) in the unused bits. We can verify whether the pointer value has been illegally rewritten by inserting a PAC into each pointer that we want to protect before writing the value of the pointer to memory and verifying the integrity of the PAC just before we use the pointer. There are usually no unused address bits in a 32-bit architecture - later we explain how we designed our PA system for 32-bit systems.

PAC is a keyed MAC based on the address of a pointer, a key and a 64-bit context. An attacker attempting to illegally rewrite a protected pointer would have to guess the correct PAC value to ensure successful authentication. To prevent an attacker from guessing the correct PAC, PA uses a key that the attacker cannot know to calculate the PAC. Also, depending on the context in which the pointer is used, PA uses a value that represents the context, such as a stack pointer, so that the PAC is different, even if the value of the pointer is the same. This makes it difficult for an attacker to guess the PAC.

Attack Scenario

The general attack scenario (not just for PA) is that the adversary can somehow exploit, for example a buffer overflow, use-after-free error or, a format string vulnerability, to alter program execution. Thanks to data execution prevention (DEP) employed in most modern systems, it is no longer effective to let the vulnerability directly alter the program code. Instead, the adversary is limited to either modify code pointers (CFI attacks, ROP and JOP), or data variables that influence the program’s decision making or leak sensitive information (non-control-data attacks and data-oriented programming, DOP). Note that in many cases, DOP attacks actually target data pointers.

If PA is used, the adversary cannot just overwrite the pointer but also needs to correctly guess the PAC associated with that pointer. More precisely, the adversary needs to guess two PACs: the first one for the pointer overwritten by the memory error (for CFI, ROP, JOP attacks, this will cause the processor to jump to a “malicious” code section), and the second one for jumping from the malicious code section back. This results in e.g. the following sequence:

- Trigger a memory error to overwrite a code pointer with the desired pointer and the forged PAC.

- Jump to the desired code section, do some bad stuff.

- Jump back to the original section, this again requires a pointer and a forged PAC.

If any of the two PACs is wrong, a fault is triggered when using the pointer. The operating system (OS) will shutdown the process and respawn it with fresh keys, meaning the adversary has to start over.

Threat Model

The threat model/attacker capabilities are formulated slightly differently between the various sources. The Google Project Zero article states that PA was designed to provide some protection against adversaries with arbitrary memory read or arbitrary memory write capabilities. The Qualcomm white paper and the conference paper by Hans Liljestrand both state that the threat model assumes that code is not writable and data not executable. But all process memory is readable, all process data is readable and writable.

In this project we consider an adversary that attempts to rewrite the return address and execute arbitrary code by exploiting a stack-buffer overflow. The adversary can:

- analyze the target binary to know the exact stack layout of functions,

- trigger any existing stack-buffer overflow,

- use stack-buffer overflow to read memory, and

- use stack-buffer overflow to rewrite the return address.

In a PA-less environment, an attacker could use a stack buffer overflow to execute arbitrary code, assuming the attacker could do such a thing. For simplicity, this project assumes only an attacker who rewrites the return address, but an attacker who tries to rewrite the code pointer or data pointer can be assumed, and it is possible to prevent it by using PA.

Integration challenges

On 64-bit systems like ARMv8.3-A, the PAC is stored in the upper, unused bits of the pointer. This is possible as the effectively used address width is 40 or 48 bits for most of today’s systems. The use of an unauthenticated pointer or a pointer for which authentication failed is signaled via translation fault in the virtual memory system. However, Ibex is a 32-bit system without virtual memory. Integrating PA into such an environment presents some unique challenges. The problem and its solution are described below.

The challenge on 32-bit systems is where to store the PAC. Ibex is a 32-bit architecture without virtual memory, so there are no unused pointer bits like on usual 64-bit systems. The upper bits of the pointer cannot be used to store the PAC, so we decided to use another memory space to store the PAC. That is, we decided to treat only authenticated pointers as 64-bit data.

And we also need a way to generate an error when PA fails. In ARMv8.3-A, when authentication fails, the upper bits are corrupted and any subsequent use of the address results in a Translation fault. Ibex doesn’t have virtual addresses, but it does have PMP (Physical Memory Protection). If authentication fails, we decided to prevent the access using PMP. We use PMP to make a region inaccessible, and pointers without authentication points to the inaccessible area. By doing this, attackers will not be able to access with unauthenticated pointers.

Auth pointers in Ibex

Ibex is a 32-bit architecture without virtual memory, so unlike the ARMv8.3-A PA, the PAC cannot be stored in the unused bits of the 64-bit pointer data. Therefore, in ibex, pointers that need to be authenticated are treated as 64-bit auth pointers which is 32-bit address data and 32-bit metadata.

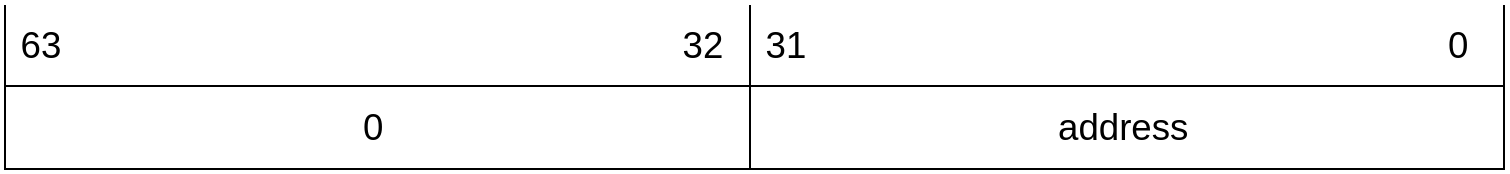

Pointers before signing

Before signing the pointer, the 32-bit address is placed in the lower bits of the 64-bit auth pointer, and the upper bits of the pointer are unused.

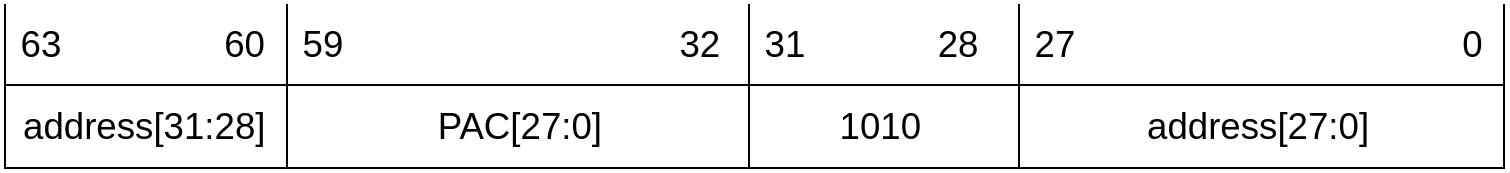

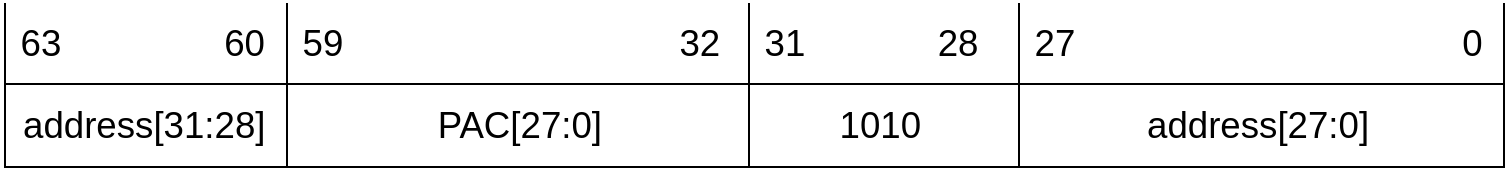

Pointers after signing

After signing the pointer, PAC and the upper bits of address are stored in the upper bits of the pointer, and we overwrite the upper bits of the lower half with a “magic” value. This magic value is used to trigger a PMP fault if the lower half of the auth pointer is used without successfully authenticating it first. In the example of this figure, the “magic” byte is set to “1010”, but in reality, the value and width of the magic byte can be freely decided at compile time.

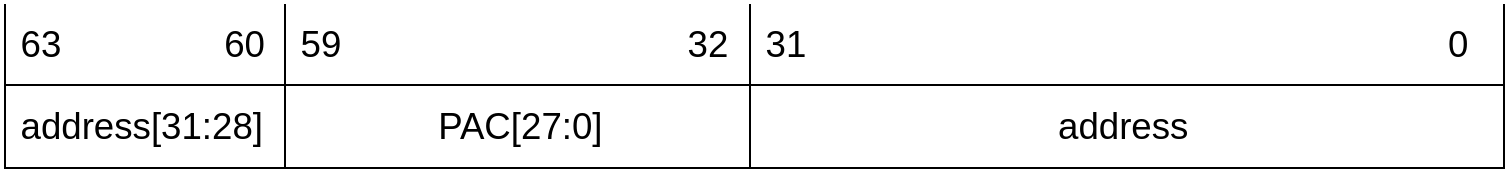

Pointers after successful authentication

If the pointer is successfully authenticated, the “magic” byte is returned to the original address value. Therefore, no PMP error occurs when accessing using this pointer.

Pointers after authentication fails

If PA fails, the pointer structure does not change. That is, the magic byte is not restored to the original value. Therefore, when the lower half of the auth pointer is used to access memory, a PMP error is triggered.

Add new custom instructions

The following new instructions have been added to implement the signing and authentication operations described in the previous section. We added two new instructions to Ibex for PA. The pac instruction adds a PAC to the pointer, and the aut instruction verifies the PAC.

We could also add combined instructions for aut and branch/jump or pac and branch/jump as in ARMv8.3-A. But for this first proof-of-concept we focused on the bare minimum to demonstrate the feasibility. Therefore, this project implements the minimum instructions, pac and aut instructions.

pac <rd>, <rs1>, <rs2>

Generate PAC. This instruction computes a pac for a pointer, using a context and key, and stores the pac to a general register. At the same time, this instruction rewrites the upper bits of the pointer to “magic” bytes.

- The pointer is in the general-purpose register that is specified by <rs1>.

- The context is in the general-purpose register that is specified by <rs2>.

- The metadata is stored in the general-purpose register that is specified by <rd>.

NOTE: This instruction has two destination registers, rs1 and rd. Also, Ibex has 2 read and 1 write port on the register file. For this reason, the pac instruction takes at least 2 clock cycles. The magic value is written to rs1 in the first clock cycle while the PAC generation is started. Once the PAC is known, it is concatenated with the pointer MSBs and written into rd. This additional latency can thus be hidden whenever a multicycle cipher core is used for generating the PAC.

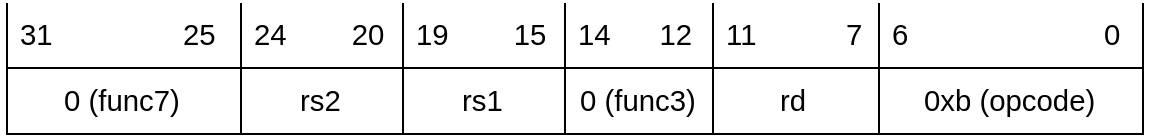

Instruction format: R type

Pseudo code

PAC = ComputePAC(x[rs1], x[rs2]);

x[rs1][31:28] = 0b1010; // magic byte

x[rd][27:0] = PAC;

x[rd][31:28] = x[rs1][31:28];

aut <rd>, <rs1>, <rs2>, <rs3>

Authenticate pointer. This instruction authenticates a pointer, using a context and key.

- The pointer is in the general-purpose register that is specified by <rs1>.

- The metadata is in the general-purpose register that is specified by <rs2>.

- The context is in the general-purpose register that is specified by <rs3>.

- The generated pointer is stored in the general-purpose register that is specified by <rd>.

If the authentication is successful, update the pointer to the correct value. If authentication fails, do nothing. Therefore, if you use this pointer later, you will get a PMP fault. In ARMv8.3-A, when authentication fails, the upper bits are corrupted and any subsequent use of the address results in a Translation fault. In Ibex, we use PMP to make a certain address space inaccessible, and an unauthenticated pointer points to the space. PMP error occurs when accessing memory using an unauthenticated pointer.

NOTE: This instruction has three source registers, rs1, rs2, and rs3. Also, Ibex has 2 read and 1 write port on the register file. For this reason, the pac instruction takes at least 2 clock cycles. Since the cipher needs the context (rs3), the PAC and a pointer (split over the two halves in the auth pointer, i.e., rs1 and rs2), we need to perform 3 reads before starting the cipher, meaning this additional cycle cannot be hidden by the cipher latency.

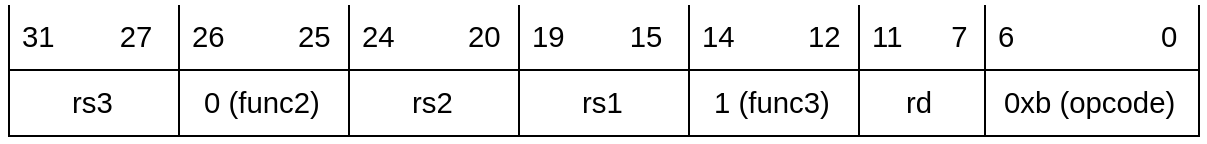

Instruction format: R4 Type (This format is only used by floating-point fused multiply-add (F) and some bit-manipulation (B) instructions.)

Pseudo code

x[rd] = Auth(x[rs1], x[rs2], x[rs3]);

bits(32) Auth(bits(64) data0, bits(32) data1, bits(32) context)

bits(32) result;

bits(64) pointer = data1<31:28>:data0<27:0>;

bits(27) pac = data1<27:0>;

if ComputePAC(pointer, context) == pac then

result = pointer; // Returns a correct pointer

else

result = data0; // Returns the same value

return result;

Compute PAC

For computing the PAC, a block cipher algorithm is used. The cipher receives a 64-bit plaintext and a 128-bit key as input, and outputs 64-bit signature data. The 64-bit plaintext is made up by concatenating the 32-bit context and 32-bit pointer. The 128-bit key is made up of 4 CSRs. 64-bit signature data is used as a PAC. Some bits of 64-bit signature data are used as PAC.

Next, we explain the block cipher algorithm used. ARMv8.3 uses QARMA as a block cipher algorithm, but a fully unrolled implementation of this cipher would probably be too costly for a core like Ibex. A previous evaluation of cipher cores for PA in embedded 32-bit processors has shown that a multicycle implementation of QARMA can be made as small as 8.9kGE and whereas the GIFT cipher requires only 5.6kGE of silicon area in a 65nm technology. GIFT turned out to be a suitable candidate for an area-efficient iterative implementation. Therefore, we adopted GIFT as the block cipher.

Update Ibex

In the chapter above, we have added the pac/aut instruction that we added for PA. In order to execute the added pac/aut instruction, Ibex needs to be updated as a work on the hardware side. The modified code repository is lowRISC/ibex and my work is here.

First, I modified the decoder to be able to decode pac/aut instructions. Next, I modified the part of the CSR register to store the key used for PA. Finally, We have connected the cipher circuit to Ibex so that the cipher circuit can communicate with Ibex using a valid/ready handshake. Of course, tests are added to verify Ibex with integrated PA.

Update LLVM

In the chapter above, we have added the pac/aut instruction that we added for PA and the modification of Ibex so that we can execute the added instruction. This chapter describes the software work. We also need to modify the compiler as a software task to insert pac/aut instructions into the function prologue and epilogue. By doing this, the compiler can automatically add the PA instruction to the program written by the user. The modified code repository is lowRISC/llvm-project and my work is here. Also, we have also modified LLVM itself so that we can build CoreMark on Ibex. The patch has been merged into upstream LLVM.

First, I modified the Machine Code (MC) layer to decode the pac and aut instructions. Next, I modified the function prologue and epilogue to insert pac and aut. And we decided to reserve the X31 register and use the X31 register to store the PAC. Therefore, in the non-leaf function X31 is overwritten, so the function prologue saves the X31 register to the stack, and the function epilogue loads PAC from the stack. Finally, I implemented the -msign-return-address option in clang, which is an option that can change the insertion frequency of pac and aut. “all” option inserts pac and aut in all functions, “non-leaf” option inserts pac and aut in only non-leaf functions, and “none” option does not authenticate pointer.

The pseudo code sequence for compiling example.c with “all”, “non-leaf” and “none” options is shown below. The “none” option does not add any processing related to PA. In comparison, the “all” option inserts pac/aut instructions in the prologue and epilogue of both the foo and bar functions. In addition, since the PAC generated by the foo function is rewritten by the bar function, the process of saving and loading the t6 (X31) register on the stack in the foo function is also added. On the other hand, in the case of the “non-leaf” option, since the bar function is the leaf function, the pac/aut instruction is not inserted in the bar function. Note: With the non-leaf option, the t6 register doesn’t have to be saved and loaded in the foo function, but we do that for ease of implementation.

example.c

int bar(int x) { return x + 1; }

int foo(int x) { return bar(x); }

“all” option

bar:

pac t6, ra, sp

addi a0, a0, 1

aut ra, ra, t6, sp

ret

foo:

pac t6, ra, sp

addi sp, sp, -16

sw ra, 12(sp)

sw t6, 8(sp)

auipc ra, 0

jalr ra

lw t6, 8(sp)

lw ra, 12(sp)

addi sp, sp, 16

aut ra, ra, t6, sp

ret

“non-leaf” option

bar:

addi a0, a0, 1

ret

foo:

pac t6, ra, sp

addi sp, sp, -16

sw ra, 12(sp)

sw t6, 8(sp)

auipc ra, 0

jalr ra

lw t6, 8(sp)

lw ra, 12(sp)

addi sp, sp, 16

aut ra, ra, t6, sp

ret

“none” option

bar:

addi a0, a0, 1

ret

foo:

addi sp, sp, -16

sw ra, 12(sp)

auipc ra, 0

jalr ra

lw ra, 12(sp)

addi sp, sp, 16

ret

Evaluation

We evaluated the overhead for PA. Moreover, in order to measure the run-time overhead by PA, we measured using CoreMark and Embench.

Hardware synthesis results

We wanted to get an estimate for the circuit area overhead of the PA integration. A synthesis run in a 65nm technology of the following core configuration was done with and without PA enabled.

| Config | Target Frequency /MHz | Area /kGE | Area Change | Max Freq /MHz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “maxperf-pmp-bmfull” | 150 | 35.91 | 150 | |

| “maxperf-pmp-bmfull” + “Pointer Authentication” | 150 | 43.16 | 20.19% | 150 |

| “maxperf-pmp-bmfull” | 300 | 43.83 | 299.33 | |

| “maxperf-pmp-bmfull” + “Pointer Authentication” | 300 | 51.68 | 18.12% | 294.45 |

The area overhead is about 20.19% when synthesizing with 150 MHz as the target. The area increased by the integration of PA is 7.25kGE of which 5.6kGE are attributed to the cipher core. The area increase due to the pipeline integration and added CSRs is 1.65kGE. Similarly, the area overhead is about 18.12% when synthesizing with 300 MHz as the target.

CoreMark

CoreMark is vendored into the Ibex repo already. To build the Ibex with “maxperf-pmp-bmfull”(RV32IMCB, 1 cycle mult, Branch target ALU, Writeback stage, 16 PMP regions) and PA, run

fusesoc --cores-root=. run --target=sim --setup --build lowrisc:ibex:ibex_simple_system --RV32M=1 --RV32E=0 --RV32B=1 --MultiplierImplementation=single-cycle --BranchTargetALU=1 --WritebackStage=1 --PMPEnable=1 --PMPNumRegions=16 --PointerAuthentication=1

The -msign-return-address option can be changed from all to non-leaf or none to change the insertion frequency of pac/aut instructions. To build the binaries with PA support, run

make -C ./examples/sw/benchmarks/coremark/ RV_ISA=rv32imc CC=${YOUR_CLANG_PATH} XCFLAGS='--sysroot=/tools/riscv/riscv32-unknown-elf --gcc-toolchain=/tools/riscv -msign-return-address=all'

The benchmark can then be executed by running

build/lowrisc_ibex_ibex_simple_system_0/sim-verilator/Vibex_simple_system --meminit=ram,examples/sw/benchmarks/coremark/coremark.elf

The result is as follows. We are comparing the custom LLVM and GCC results. Comparing LLVM with each other, it can be seen that the performance degradation due to PA is 5.92% with the configuration of LLVM(all) and 3.06% with the configuration of LLVM(non-leaf). Also, by comparing LLVM(none) and LLVM(none, -ffixed) which uses none and -ffixed-x31 options at the same time, we have evaluated how the performance is affected by not using X31 register. The performance degradation due to not using one register is 2.12%, and it can be seen that reserving the X31 register to save the PAC has some performance impact.

In addition, we have used GCC to validate the performance and that there is a significant gap that is mostly due to CoreMark-specific optimizations inside GCC. For this reason we have decided to also investigate a different benchmark suite, i.e., Embench. Embench results are presented in the next section.

We can also use pac/aut instructions executed results to estimate how performance will be impacted when reducing the cipher core latency. it is interesting to understand what the performance would be with a lower-latency cipher core to trade off area vs. performance. The last section of this chapter describes that estimate.

| Config | LLVM(all) | LLVM(non-leaf) | LLVM (none, -ffixed-x31) | LLVM (none) | GCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoreMark/MHz | 2.035 | 2.097 | 2.118 | 2.163 | 2.994 |

| pac instructions executed | 17508 | 4347 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| aut instructions executed | 17508 | 4347 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Embench

Embench is not yet vendored into the Ibex repo, but Greg has it ready on one of his branches. Go to examples/sw/benchmarks/embench-iot and run run_build.sh and then run_benchmark.sh.

To build the binaries with PA support, open

examples/sw/benchmarks/embench-iot/run_build.sh

and change the command on line 7 to

./build_all.py --clean --arch riscv32 --chip speed-test --board ibex_ss_verilator --cc ${YOUR_CLANG_PATH} --cflags '--sysroot=/tools/riscv/riscv32-unknown-elf --gcc-toolchain=/tools/riscv -ffixed-x31 -msign-return-address=none' --ld riscv32-unknown-elf-gcc --verbose

The result is as follows. We are comparing the custom LLVM and GCC results. Comparing LLVM with each other, the average performance degradation is 0.9 to 5.7%. There is almost no performance difference between LLVM and GCC in this benchmark. In CoreMark, LLVM had lower performance than GCC, but in Embench, we were able to achieve the same or better performance.

| LLVM(all) | LLVM(non-leaf) | LLVM (none) | GCC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aha-mont64 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 1.28 | 0.95 |

| crc32 | 1.48 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.04 |

| cubic | 1.16 | 1.16 | 1.16 | 1.16 |

| edn | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 0.89 |

| huffbench | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.78 |

| matmult-int | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.91 |

| minver | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.07 |

| nbody | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.04 |

| nettle-aes | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 1.00 |

| nettle-sha256 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| nsichneu | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.96 |

| picojpeg | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.96 |

| qrduino | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.96 |

| sglib-combined | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.99 |

| slre | 1.21 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 0.91 |

| st | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.09 |

| statemate | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| ud | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.99 |

| wikisort | 0.99 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.89 |

| Mean | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.97 |

Evaluation using different cipher core latencies

In the above evaluation of CoreMark and Embench, we evaluated using a cipher core that has an execution latency of 5 cycles for the pac and aut instructions. Therefore, we evaluated CoreMark and Embench to show how the performance increases when using different cipher core latencies. However, in this evaluation, cipher cores with different latencies were not actually implemented, but we evaluated using mathematical expressions. Since we have not actually implemented it, it is expected that the hardware area of a cipher core with low latency will increase, but we have not been able to evaluate how much the area will increase.

The results of evaluation using different crypto core latency are shown below. The results below show the CoreMark/Embench performance drop when the latency of the cipher core is changed for LLVM(all) and LLVM(non-leaf) respectively. In the case of LLVM(all), it was found that changing the latency from 5 to 2 reduced the performance drop by about 2% for both CoreMark and Embench. Also, in the case of LLVM (non-leaf), changing the latency from 5 to 2 reduced the performance drop of CoreMark by 2.18%, and reduced the performance drop of Embench by about 0.43%

| Config | LLVM(all) | LLVM(all) | LLVM (all) | LLVM (none) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latency of pac/aut instruction | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| CoreMark Performance Drop | 5.92 % | 4.56 % | 3.86 % | 0.00 % |

| Embench Performance Drop | 5.01 % | 3.56 % | 2.80 % | 0.00 % |

| Config | LLVM(non-leaf) | LLVM(non-leaf) | LLVM (non-leaf) | LLVM (none) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latency of pac/aut instruction | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| CoreMark Performance Drop | 3.06 % | 1.62 % | 0.88 % | 0.00 % |

| Embench Performance Drop | 1.79 % | 1.50 % | 1.36 % | 0.00 % |

Conclusion

In this document, we have presented a proof-of-concept integration of PA into Ibex. To our knowledge, this is the first implementation of PA into a 32-bit embedded processor core.

During this Google Summer of Code project, we have done the following tasks: 1. We have integrated an existing block cipher for generating pointer authentication codes (PACs) into the Ibex pipeline. 2. We have implemented new custom instructions for generating and authenticating PACs using this block cipher and a key provided via custom control and status registers (CSRs). 3. We have added support in the LLVM compiler toolchain for these instructions. 4. We have implemented a new compiler pass in the LLVM compiler toolchain to automatically sign and authenticate return addresses. 5. We have performed an in-depth performance analysis of the resulting system.

Area goes up by 20.19% and performance drops by only 1.79 to 5.92% using a five-cycle latency GIFT cipher core. Using a lower-latency cipher core implementation, the performance drop could be reduced from 3.86% to 0.88% but comes at the cost of higher area overhead. We have shown that PA is feasible for embedded, 32-bit, microcontroller-type cores at reasonable performance/area overhead.

Although only the return address authentication is supported in the GSoC2020 project, PA has the potential to also protect more than return addresses and that this should further be investigated. Please look forward to our future work.

Acknowledgment

Finally, I would like to thanks people:

- My mentors, Pirmin Vogel, Luís Marques and Sam Elliott

- lowRISC community

- OpenTitan community

GSoC has finished, but I’d like to continue this project and make further progress.

References

- ARM A64 Instruction Set Architecture ARMv8, for ARMv8-A architecture profile

- Qualcomm Whitepaper on Pointer Authentication

- Liljestrand et al., “PAC it up: Towards Pointer Integrity using ARM Pointer Authentication”, USENIX Security, 2019

- Azad, “Examining Pointer Authentication on the iPhone XS”, Google Project Zero, 2019